Objective

Welcome to the Identify Heat-Related Vulnerabilities and Impacts module! There are a wide range of reasons why a person or community may be at greater risk of heat-related illness, injury, or death. For example, people unable to access cool spaces or afford air conditioning due to their economic status may experience greater risks.

To prioritize and implement projects and investments towards equitable outcomes, you should identify and connect with the populations in your jurisdiction that are at greater risk of heat-related impacts. This will also allow you to partner with these groups and take a community-led approach in your projects. In this module, you will define vulnerability in your context and subsequently map community groups that are most vulnerable to heat impacts based on geography or underlying social, economic and health characteristics.

This module can build on the outputs from the previous module, Conduct a Baseline Heat Risk Assessment.

Essential Actions, Outputs, and Outcomes from this Module

Actions

-

Gather data sources specific to your area that provide information on social and physiological vulnerability factors like age, income, and access to air conditioning and cool spaces.

-

Draw on this data to produce a document that provides an overview of the most heat-vulnerable populations in your jurisdiction. If possible, map and overlay this data on your temperature/population maps to create a series of maps or in one combined vulnerability index.

Outputs

-

A table or short document describing which populations are most heat-vulnerable in your jurisdiction and why.

-

If possible, a temperature map(s) with data layers relevant to vulnerability or heat vulnerability index mapped on it that informs investments in heat resilience.

Outcomes

-

Understand the underlying economic, social, and health characteristics that affect heat risk among local residents.

-

Identify who is most vulnerable to heat in your jurisdiction.

-

Identify where the most dangerous heat exposure is in your jurisdiction and why.

-

Understand how policies and plans can prioritize heat-vulnerable populations.

Overview

The Essential Actions, Outputs, and Outcomes include the core elements of the more comprehensive approach described throughout the rest of the module. We know that time, resources, and capacity can limit the breadth and depth of interventions you undertake. Simply beginning to explore these modules and consider what solutions are appropriate for your context is a critical step toward building your jurisdiction’s heat resilience. At any point, reach out to Arsht-Rock using the contact form at the bottom of the page with questions and comments.

Factors in heat-related vulnerability

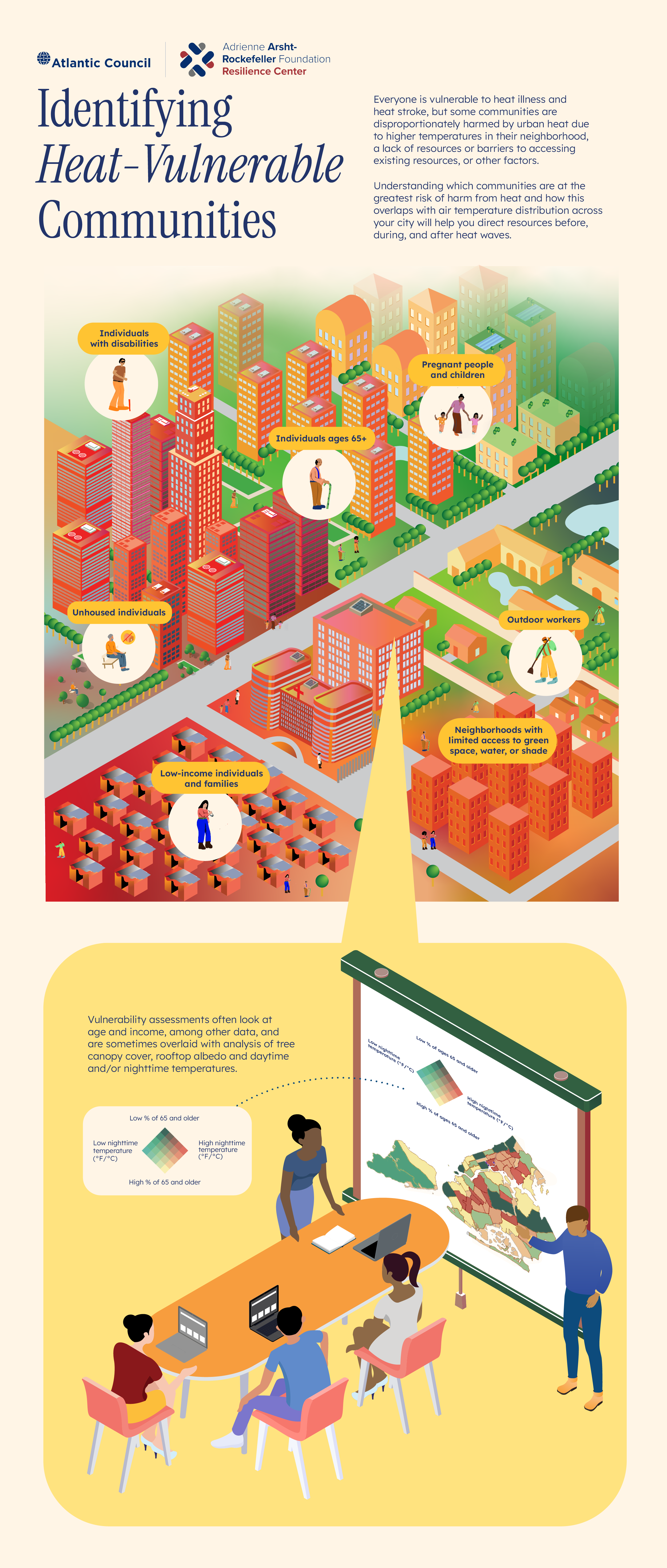

All people are at risk of heat-related illness or death, but to varying extents. Many social, economic, and physiological factors affect a person or community’s risk of heat-related illness or death. These include age, caste/class, community cohesion, cultural norms, discrimination/marginalization, gender, income and wealth, language, profession, race, pre-existing health conditions, use of certain prescription drugs, and access to cool spaces and potable water.

Older adults

Individuals over 65 years of age are less physiologically adaptable to heat.

People living alone

People living alone, particularly individuals with disabilities, may be less likely to receive life-saving information or assistance during a heat wave.

Newborns and children under 5 years

Newborns and children under 5 are susceptible to heat impacts and dependent on others for care and hydration.

Women

Depending upon the cultural norms of the area or household, women may be expected to stay indoors with greater frequency, engage in heat-exposed outdoor or indoor labor (e.g., cooking near a hot stove) or wear heavy clothing.

Pregnant people

During pregnancy, people’s bodies are less able to regulate core body temperature, posing risks to the pregnant individual that include hospitalization, preterm birth, miscarriage, and death.

People with underlying medical conditions

Heat can exacerbate or compound pre-existing medical conditions, or negatively impact people who take medications that make them more susceptible to heat’s effects.

Unhoused people

Individuals without consistent access to housing may not have access to shelter, shade, air-conditioning, or water.

Outdoor workers

Outdoor work often involves exposure to hot temperatures and direct sunlight, and can regularly include physical strenuous labor that raises core temperatures.

Non-native language speakers

Those who do not speak the predominant language may lack access to the latest heat warnings and information on staying safe during heat waves in their primary language.

Resources

Extreme Heat Toolkit

- United States

See page 9 of the Wisconsin Climate and Health Program’s Extreme Heat Toolkit for more information on identifying populations who are vulnerable and why.

Heatwave Guide for Cities

- Global

See page 18 of the Red Cross Red Crescent Climate Centre’s Heatwave Guide for Cities for a helpful one-pager on who is vulnerable and why.

Climate Resilience for Frontline Clinics Toolkit

- Global

For guidance on how prescription drug use, chronic health conditions, and pregnancy can interact with heat, see the “Heat” section of the Climate Resilient for Frontline Clinics, produced by Harvard Chan C-CHANGE and Americares.

Identifying communities at high risk of harm from heat

Vulnerability assessments often analyze how temperature is distributed throughout an area (see Conduct a Baseline Heat Risk Assessment), age, income, and other factors such as access to cooling (cooling centers, tree canopy coverage, etc.) and energy burden.

Researchers often partner with governments to develop detailed heat vulnerability maps and future projections of where heat may have the worst impacts. Involving communities most impacted by heat (e.g., through a survey or participatory assessment process) can help ensure that your analysis is accurate and grounded in people’s lived experiences. When beginning a vulnerability assessment, consider the time and resources you have for outreach and communication to create a practical plan of action for community engagement.

Resources

Urban Heat Mapping Framework

- Global

For a practitioner-oriented overview of heat mapping approaches, technologies, and considerations, see Arsht-Rock’s Urban Heat Mapping Framework.

City Resilience Toolkit

- Global

For checklists and descriptions of government engagement and vulnerability assessment processes, see pages 10-12 of the Natural Resources Defense Council’s City Resilience Toolkit: Responding to Deadly Heat Waves and Preparing for Rising Temperatures.

Feasibility Study on Heatwave in Dhaka

- Bangladesh

For a methodology used by the Red Cross in Dhaka, Bangladesh to assess the impact of heat waves on specific populations (e.g., residents of informal settlements and rickshaw drivers), see pages 17-24 of the Feasibility Study on Heatwave in Dhaka.

Impact Forecast Mapping

- Vietnam

For an example of using software and geographic information system mapping to identify vulnerable areas in Hanoi, Vietnam, see page 2 of Impact Forecast Mapping: Identifying Urban Areas Most Vulnerable to Heat Wave, produced by the German Red Cross.

Recognizing differences between jurisdictions

Each jurisdiction faces unique heat-related challenges. Consider how geographic and climatic factors such as nearby coasts or mountain ranges impact your region. Population and economic factors are important as well. For example, one city may have many outdoor workers; another may have a tourist season, necessitating planning measures to protect non-residents; another may include many individuals who are currently or have been historically marginalized or harmed by racism and other forms of discrimination. Marginalization and discrimination can already be negatively impacting population health, access to resources, and trust in government, and this may be further exacerbated by extreme heat.

Temperatures can be reduced by water features or green spaces. However, areas with large parks or ponds are also popular to live in (and new development of these spaces is often directed toward wealthier communities), so low-income populations are often priced out or unable to move into the area to begin with, forcing them further away into hotter areas. Additionally, green spaces may not be accessible by all residents. For example, safety concerns or cultural factors can prevent women from accessing dense parks and forests by themselves.

Other factors that can contribute to a jurisdiction’s heat related challenges include community demographics, proximity to polluting resources and compounding hazards such as storms, floods, and droughts.

Resources

Urban Heat and Equity: Experiences from C40’s Cool Cities Network

- Global

For an example of several cities examining who is most vulnerable in their communities, see pages 6-16 of Urban Heat and Equity: Experiences from C40’s Cool Cities Network, produced by C40.

Mapping the Vulnerability of Human Health to Extreme Heat in the US

- United States

For a list of key recommendations and questions to consider when conducting vulnerability mapping, see pages 44-48 of the US Environmental Protection Agency’s Mapping the Vulnerability of Human Health to Extreme Heat in the US.

Centering Equity to Address Extreme Heat

- United States

For a list of equity-related questions to consider when assessing community vulnerabilities, see page 12 of the Urban Institute’s brief Centering Equity to Address Extreme Heat.

Greening in Place: Protecting Communities from Displacement

- United States

For a set of anti-displacement policies and program recommendations, see page 13 of Greening in Place: Protecting Communities from Displacement by the Audubon Center at Debs Park, Public Council, and SEACA.

Using vulnerability assessment outputs

Vulnerability assessments that are rooted in engagement with heat-affected communities should guide your decision-making process throughout the project or planning process. Generally, who is vulnerable to heat, where they are located, and when they are most at risk should be made clear by the vulnerability assessment.

For example, Western Sydney, Australia conducted a series of workshops and interviews with stakeholders to understand who is most impacted by heat and how. This led to the realization that the urban heat island effect was a clear concern, and as a result, the city’s action plan prioritized reducing urban heat island impacts through the planning and design of new buildings. Using vulnerability assessments can build a clear and specific case for investing in protecting people’s health and livelihoods.

The way that you define vulnerability will define your metrics of success, and engagement with vulnerable populations should not end after the planning process. Community-centered or community-led efforts will be more likely to be sustainable and to succeed, as community members invest in the project and deliver critical feedback on what aspects are working and where improvements could be made.

Resources

Beating the Heat

- Global

To read more about the example of Western Sydney, see pages 64-66 of Beating the Heat: A Sustainable Cooling Handbook for Cities published by the UN Environment Programme and developed by the Cool Coalition, RMI, Global Covenant of Mayors for Climate & Energy, Mission Innovation, and Clean Cooling Collaborative.

Heatwaves and Homelessness

- Australia

For an example of how Melbourne has focused on homeless populations impacted by heat, see the Australian city’s strategy Heatwaves and Homelessness.

Heatwave Guide for Cities

- Global

To find additional case studies of heat vulnerability assessments, see pages 36-37 of the Red Cross Red Crescent Climate Centre’s Heatwave Guide for Cities.

Common challenges

A common challenge in producing a vulnerability assessment is a lack of community trust in government or outside researchers. Appropriate and thorough community engagement and time and resources to devote to the process are essential, but it is important to acknowledge that certain communities may not have been previously engaged in this type of assessment, leading to a lack of trust. Even if residents have previously been engaged in similar assessments, they may be reluctant to invest more time before seeing that their engagement is yielding results. Before approaching community members, work with community leaders and organizations to understand historical relationships and previous engagement efforts.

When developing a vulnerability map, there may or may not be underlying high quality data available (e.g., demographic data, temperature data) or the resources and capacity needed to collect or produce and leverage that data. Identifying partners with similar goals or research capacity can help fill this gap.

Congratulations! You’ve completed Identify Heat-Related Vulnerabilities and Impacts.

Review the Essential Actions, Outputs, and Outcomes from this Module or proceed to the next module.